Download the PDF version of this Issue Brief.

Also, watch our video on Proposition 5.

Proposition 5, which will appear on the November 6, 2018 statewide ballot, would make significant changes to California’s local property tax system. Local property taxes provide resources that go to support a broad range of local services and systems across our state. Prop. 5 would expand special rules that allow certain property owners to lower their property taxes. The reduced property tax revenue under Prop. 5 over time would result in losses of approximately $1 billion annually for cities, counties, and special districts and similar reductions in state funding available for public services and supports in most years, other than for K-14 education (K-12 schools and community colleges). In addition, Prop. 5 would reduce local funding for some K-14 districts. The ultimate effect of Prop. 5 would be to expand tax breaks for older, wealthier California homeowners at the expense of other homeowners, including those who are younger and less affluent. Prop. 5 is sponsored by the California Association of Realtors and supported by the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association. This Issue Brief provides an overview of the measure; discusses what it would mean for homeowners, housing supply and affordability, and funding for public services; and examines other policy issues the measure raises in order to help voters reach an informed decision.

What Would Proposition 5 Do?

Prop. 5 would amend both the state Constitution and state law to expand special rules for assessing certain property values that are the basis for calculating property taxes. Property taxes support services provided by local governments, such as cities, counties, special districts, and school districts. When local governments levy taxes on property owners, these taxes equal the taxable value of the property multiplied by a property tax rate. Prop. 13, approved by California voters in 1978, capped property tax rates at 1%, with limited exceptions, and replaced the practice of reassessing the taxable value of property each year at fair market value (what the property could sell for) with a system based on cost at acquisition (what the owner paid for the property).[1] Under Prop. 13, increases in the taxable value of property are limited to an annual inflation factor of no more than 2%, and property is only assessed at market value for tax purposes when it changes ownership.

In the 40 years since Prop. 13 passed, California voters have approved several ballot measures that apply special property tax rules (some of which are described in the following section) to certain types of property owners. Beginning on January 1, 2019, Prop. 5 would expand several of these special rules and apply them to:

- Homes purchased or constructed by existing California homeowners who are age 55 or older or who are severely disabled.

- Any property purchased or constructed to replace property substantially damaged or destroyed by a disaster.[2]

- Any property purchased or constructed to replace “qualified contaminated property,” such as property that is no longer habitable or usable due to the presence of toxic or hazardous materials.[3]

Proposition 5 Would Expand Special Rules for Certain Homeowners

Currently, special rules allow California homeowners who are age 55 or older or who are severely disabled to transfer the taxable value of a home they sell to a new home within the same county, provided that the market value of the new home is the same or less than the market value of the home they sold.[4] California counties also may allow older or disabled homeowners to transfer the taxable value of homes sold in a different county to a home purchased in their county. Currently, 11 counties accept these inter-county transfers.[5] Older homeowners who transfer the taxable value of existing property to new homes purchased within or across counties may only do so once in their lifetime.[6] In most cases, these special rules mean that homeowners age 55 or older who purchase a new home pay less in property taxes than a younger person would pay for the same home, because its market value is often greater than the taxable value of the home sold by the older homeowner.

Prop. 5 would expand the special rules for California homeowners who are age 55 or older or who are severely disabled. Specifically, Prop. 5 would allow these homeowners to:

- Purchase or construct a new home that is more expensive than the home they sell, but pay property taxes that are tied to the taxable value of the old home.

- Purchase or construct a new home that is less expensive than the home they sell and reduce the taxable value of the new home below the taxable value of the old home.

- Transfer the taxable property value under Prop. 5’s special rules anywhere in the state, regardless of whether the county where the new home is located currently allows such transfers.

- Transfer the taxable property value under Prop. 5’s special rules to new homes an unlimited number of times, rather than just once per lifetime as under current law.

Proposition 5 Would Expand Special Rules for Any Owner of Contaminated Property or Property Destroyed by a Disaster

Under current law, special rules allow any owner of contaminated property or any owner of property that is substantially damaged or destroyed by a disaster to transfer its taxable value to a replacement property — regardless of whether this property is acquired or newly constructed — within the same county based on certain conditions. Owners of contaminated property may transfer its taxable value to a replacement property if the market value of the replacement property is the same or less than the market value of the contaminated property, assuming the property had not been contaminated.[7] Owners of property destroyed by a disaster may transfer its taxable value to a replacement property assuming the replacement property is comparable in size, utility, and function to the property it replaces and does not exceed 120% of the market value of the replaced property in its pre-damaged condition.[8]

Prop. 5 would expand the special rules for owners of contaminated property or property that is substantially damaged or destroyed by a disaster. Specifically, Prop. 5 would allow owners of contaminated property to purchase or build replacement property that is more expensive than the contaminated property, but pay property taxes that are tied to the taxable value of the contaminated property. Prop. 5 also would expand the special rules for owners of property destroyed by a disaster and allow them to transfer the taxable value of the destroyed property to any replacement property regardless of its size or value. Prop. 5 also would allow the assessment of the value of contaminated or destroyed property under its special rules to be transferred anywhere in the state regardless of whether the county where the new property is located allows such transfers from other counties.

Proposition 5 Would Provide Additional Tax Breaks for Eligible Properties

Prop. 5 would establish two formulas to calculate the taxable value of an eligible property. (As previously described, an eligible property is a new home purchased by an older or disabled homeowner or a property that replaces a contaminated property or property destroyed in a disaster.) Both formulas would tie the taxable value of an eligible property to the owner’s prior property.

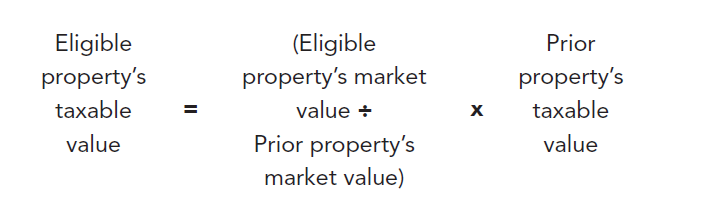

The property tax formulas established by Prop. 5 would be based on three factors: the prior property’s market value (the price it sold for), the eligible property’s market value (what it was purchased for), and the prior property’s taxable value. One formula would apply when the market value of the eligible property is greater than the prior property, and the other formula would apply when the market value of the eligible property is less than the prior property.

Prop. 5 Would Establish a Formula That Reduces the Taxable Value of an Eligible Property if It Is More Expensive Than the Prior Property

If an eligible property is more expensive than the prior property, the taxable value of the eligible property would equal the difference between the eligible property’s market value and the prior property’s market value, added to the taxable value of the prior property.

Prop. 5 Would Establish a Formula That Reduces the Taxable Value of an Eligible Property Below the Taxable Value of the Prior Property if the Eligible Property Is Less Expensive Than the Prior Property

If an eligible property is less expensive than the prior property, the taxable value of the eligible property would equal the market value of the eligible property divided by the market value of the prior property, multiplied by the taxable value of the prior property.

What Would Proposition 5 Mean for Homeowners?

Proposition 5 Would Expand Tax Advantages for Older Homeowners

Under current law, special rules provide a tax break to California homeowners who are age 55 or older by allowing them to transfer the taxable value of a home they sell to a new home they purchase, but only if the market value of the new home is the same or less than the market value of the home they sold.[9] These rules usually provide a tax advantage for older homeowners, who pay less in property taxes than a younger person would pay for the same home. This is because the market value of the home that is purchased by the older homeowner is often much greater than the taxable value of the home that is sold.

Prop. 5 would expand this annual tax break in two ways. Prop. 5 would:

- Increase the annual tax break for older homeowners who purchase homes that are worth the same or less than the market value of the home they sold. Under current law, an older Californian who sells a home that has a taxable value of $200,000 and purchases a new home for $450,000 pays $2,000 in property taxes ($200,000 x 1%) annually as long as the prior home sold for more than $450,000.[10] In comparison, people under the age of 55 would pay $4,500 in property taxes ($450,000 x 1%) annually for the same home. Prop. 5 would establish a new formula that would actually increase this $2,500 annual tax advantage for older homeowners. For example, under the new formula, an older Californian who sells a $500,000 home that has a taxable value of $200,000 and purchases a new home for $450,000 would pay $1,800 in property taxes annually, increasing the tax break under current law by $200 annually (see Figure 1).

- Allow older homeowners to purchase a new home that is more expensive than the home they sell and tie the property taxes for the new home to the taxable value of the old home. For example, an older Californian who sells a $1.4 million home with a taxable value of $200,000 and purchases a new home for $1.5 million would only pay $3,000 in property taxes annually, a $12,000 tax advantage compared to someone under the age of 55 who would pay $15,000 in property taxes annually ($1,500,000 x 1%) for the same home (see Figure 2). In other words, in this example, the older homeowner could purchase a home with a value more than seven times larger than the taxable value of the current home, with only a relatively modest increase in property taxes.

The expansion of these tax breaks under Prop. 5 would provide even more substantial benefits to older homeowners who already, under current law, receive preferential treatment that allows them to pay far less in annual property taxes than younger homeowners.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Proposition 5’s Annual Tax Breaks Would Increase as the Market Value of a Prior Home Increases

Whether older homeowners purchase property that is more or less expensive than the market value of their prior home, the tax break provided by Prop. 5 would increase as the market value of the prior property increases. Using the prior example, under Prop. 5 an older Californian who sells a home that has a taxable value of $200,000 and purchases a new home for $450,000 would pay $1,800 in property taxes annually if they sold their prior home for $500,000. However, if the same homeowner sold their prior home for $1.4 million, they would pay less than $650 in property taxes annually (see Figure 1). Similarly, under Prop. 5, an older Californian who sells a $500,000 home with a taxable value of $200,000 and purchases a new home for $1.5 million would pay $12,000 in property taxes annually, whereas if the same homeowner sold their prior home for $1.4 million, they would pay $3,000 in property taxes annually (see Figure 2). As a result, Prop. 5 would most benefit Californians who have seen substantial increases in their home values, such as people from areas of the state where home values have increased rapidly relative to other areas and those who have owned their properties for longer periods of time.

Proposition 5 Would Provide Larger Tax Breaks for Older, Wealthier Californians Who Can Afford More Expensive Homes

The tax breaks Prop. 5 proposes for California homeowners who are age 55 or older would be larger for newly purchased homes that are more expensive than prior homes than they would be for newly purchased homes that are less expensive than prior homes. For example, under Prop. 5 an older Californian who sells a home with a market value of $500,000 and a taxable value of $200,000, and then purchases a new home for $450,000 would receive an annual tax break of $200 compared to current law (see Figure 1). By contrast, the annual tax break would be far larger — $3,000 — if the same Californian purchased a new home for $1.5 million (see Figure 2). As a result, Prop. 5 would provide larger tax breaks to wealthier Californians who are able to afford more expensive homes.

Proposition 5 Disadvantages Younger, Less Wealthy Homeowners

As noted in the sections above, Prop. 5 would expand tax advantages for older homeowners, allowing them to pay less in annual property taxes for a newly purchased home than younger homeowners would pay for the same home. These new tax advantages would be larger for older homeowners whose prior home has experienced the most substantial gains in value prior to being sold. The annual tax advantages would be larger for older, wealthier homeowners able to purchase more expensive homes. Prop. 5 also would remove limits on how many times eligible homeowners can transfer the taxable value of their home. In other words, eligible homeowners could carry forward the tax break to all future home purchases.

Younger, less wealthy homeowners, would also be adversely affected by a potential increase in home prices that could result from Prop. 5.[11] This is because the tax advantage provided to older, wealthier homeowners means that they would have more annual resources at their disposal to use in negotiating the purchase price of new homes. Using the earlier example, an older Californian who sells a $1.4 million home with a taxable value of $200,000 and purchases a new home for $1.5 million would pay only $3,000 in property taxes annually. Someone under the age of 55 would pay $15,000 in property taxes each year — a $12,000 annual tax advantage for the older homeowner. That annual tax advantage would likely be used in negotiating the purchase price of new homes, particularly in highly competitive housing markets, and could result in an increase in housing prices.

Prop. 5 would also reduce local property tax capacity, as noted in the section below on local government implications. As a result, local governments would necessarily rely more heavily upon younger and less wealthy homeowners to pay for local services, including the costs of infrastructure financed through local government general obligation bonds that are also tied to local property values.[12]

Characteristics of Eligible Homeowners Under Proposition 5

Homeowners who would be eligible for the special property tax rules under Prop. 5 include people age 55 or older as well as those with severe disabilities.[13] Of these two major eligible groups, older homeowner households make up by far the largest share. Statewide, about 4.1 million older or disabled homeowner households would be eligible under Prop. 5, of which 4.0 million are age-eligible (97.4%) and roughly 100,000 are eligible due to disability only (2.6%), according to a Budget Center analysis.[14]

In fact, a majority of California’s 7.0 million homeowner households (59.6%) would meet Prop. 5’s eligibility criteria. In a given year, however, only a small fraction of these eligible homeowners would be expected to sell their homes, buy new homes within California, and claim the new property tax reductions that would be allowed under Prop. 5.[15]

Homeowner households that would be eligible for special property tax rules proposed by Prop. 5 are relatively advantaged. Their median household income of $77,000 is 14.9% greater than the overall statewide median household income ($67,000). Moreover, eligible homeowner households headed by someone who is younger than the traditional retirement age — those with household heads under age 65 — have a median household income of nearly $100,000 ($98,900), meaning that about half have annual incomes greater than $100,000. These relatively high incomes translate into relatively low poverty rates, as well. While about 1 in 5 heads of household in California overall (19.0%) are in poverty based on the California Poverty Measure (CPM) — an improved poverty measure that accounts for housing costs — only about 1 in 9 homeowner household heads eligible under Prop. 5 (11.8%) are in poverty under the same measure.[16] In terms of sources of income, about 1 in 7 eligible homeowner households (15.0%) receive more than $15,000 in annual investment income. Moreover, only 11.6% of Prop. 5-eligible households depend on fixed retirement or disability payments from Social Security and/or Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for more than three-quarters of their total household income.

The characteristics of Prop. 5-eligible homeowner households contrast sharply with those of older renter households in California, who are much less economically secure. Renter households headed by individuals age 55 or older have a median income of only $32,900, roughly half the overall statewide median household income. Older renter households also have a much higher poverty rate, with 1 in 3 (33.3%) older renter household heads living in poverty based on the CPM (see Figure 3). They are much more likely to rely on fixed Social Security or SSI payments than Prop. 5-eligible homeowners, with more than 1 in 4 older renter households (27.3%) relying on Social Security and/or SSI for more than three-quarters of their household income, including 43.7% of renters with a head of household age 65 or older.

Figure 3

In terms of race and ethnicity, the homeowners eligible under Prop. 5 are primarily white. Nearly two-thirds (64.0%) of eligible household heads are white (and not Latino). In contrast, less than half of all California households (48.3%) are headed by someone who is non-Latino white, while the majority (51.7%) are headed by a person of color. Older renter households are largely similar to California households overall in terms of race and ethnicity.

The advantaged position of Prop. 5-eligible households is perhaps clearest, however, when examining their wealth in the form of the value of their homes. Most are long-term homeowners who have had the opportunity to accrue significant home equity as California’s housing prices have grown over time. About half of eligible homeowner households have lived in their homes for at least 20 years, during which time the median price of a single-family home in California has increased by 280%, or 1.8 times the rate of inflation, according to a Budget Center analysis of home price data from the California Association of Realtors. More than a quarter of eligible households (26.1%) have lived in their homes for at least 30 years.

In terms of the value of their homes, about half of eligible homeowner households (47.7%) own homes worth a half-million dollars or more. About 1 in 7 (13.9%) own homes worth $1,000,000 or more. Furthermore, nearly 4 in 10 eligible homeowners (38.8%) own their homes free and clear, with no mortgage, so that they stand to receive the full appreciated value of their homes if they sell. The typical home values of eligible homeowners vary by region, but home values are relatively high in the top two regions with the largest number of eligible homeowners: Los Angeles and the South Coast, and the San Francisco Bay Area (see Table 1).

Table 1

Because so many of the homeowners eligible under Prop. 5 have lived in their homes for many years, their property taxes tend to be significantly lower than the property taxes paid by younger homeowners who would not be eligible for special property tax rules under Prop. 5. This is because Prop. 13 (1978) caps the allowed increase in annual property taxes at a rate that is typically lower than the annual increase in a home’s market value, as described above. As a result, in 2016 the older and disabled homeowner households who would be eligible under Prop. 5 paid median property taxes of $2,950, equal to only about three-quarters of the median taxes paid by younger homeowners ($4,050).

In summary, taken as a whole the older and disabled homeowner households who would be eligible for special property tax rules under Prop. 5 have higher incomes and lower poverty rates than California households overall, and much higher incomes and lower poverty rates than older renter households. Prop. 5-eligible households are also more likely to be headed by white individuals and much less likely to be headed by people of color than California households overall. Most are long-term homeowners, and nearly half own homes worth a half-million dollars or more. At the same time, their current typical property tax payments are significantly lower than the typical property taxes paid by younger homeowners, who would not be eligible for the special tax advantages provided by Prop. 5.

Though Prop. 5-eligible homeowners as a group are relatively well-off economically, there are some older and disabled homeowners, and homeowners affected by unexpected disasters, with low fixed incomes who would be unable to pay higher property taxes out of their existing incomes if they moved. As a result, they may feel “stuck in place” in homes that are larger than they need or not as close to family or other supports as they would prefer. However, many of these homeowners could likely take advantage of existing special property tax rules for older and disabled homeowners and find suitable new homes of equal or lesser market value within the county where they currently live, or within one of the counties that allows for inter-county transfer of existing property taxes for older and disabled homeowners under current law (as described above). As a result, they could meet their housing needs without the new tax advantages that would be created by Prop. 5. Moreover, many of these homeowners have built up significant home equity over time, and could reasonably afford to pay higher property taxes by withdrawing some of their equity when selling their homes and using some of those funds each year to cover the cost of higher property taxes for their new homes.

For the small number of older, disabled, and disaster-affected homeowners who are truly “stuck in place” — those with low fixed incomes and limited home equity who cannot find a suitable new home where they can carry over their current property tax amounts within the geographic limits allowed by current law — more narrowly targeted policies could be developed that would help these homeowners specifically. Better targeted policy approaches, such as tax credits for homeowners who meet specific income and asset limits as well as criteria related to age, disability, and/or disaster, would allow for more efficient use of limited public resources, and would be preferable to Prop. 5, which offers tax breaks to many homeowners who do not need public financial assistance, at the expense of local and state government budgets and the key services they support. Alternatively, if the policy goal is to address the housing needs of older Californians with low or fixed incomes, focusing on older renter households would make much more sense than focusing on older homeowners, since older California renters, as a group, face much greater economic insecurity.

How Would Proposition 5 Affect Housing Mobility, Supply, and Affordability?

Many parts of California face a range of housing affordability challenges, including a lack of supply to meet the demand for housing, higher housing prices resulting from increased competition for available housing, and a lack of housing mobility because people are less able to afford changing homes and/or are unable to find available housing. How would extending tax breaks to older homeowners affect these forces?

As noted earlier, Prop. 5 could lead to an increase in home prices. [17] The annual tax advantage for older homeowners would likely be used in negotiating the purchase price of new homes. Because Prop. 5 changes existing law to allow older homeowners to base their property tax bill for a more expensive newly purchased home on their prior home, the effect on home prices might be particularly notable for already higher-priced markets. In addition, as noted earlier, the tax advantages from Prop. 5 will largely accrue to wealthier, older homeowners who can already afford to move.

In terms of housing supply and mobility, the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) projects that the number of potential movers as a result of Prop. 5 could increase by “a few tens of thousands” and that there could be some effect on home building.[18] But, the potential impact would be small relative to the total number of homeowners in California and the demand for housing. California has 7 million homeowner households and the state Department of Housing and Community Development estimates that California needs 1.8 million new homes to meet demand by 2025.[19] If some increase in home building results from increased demand from Prop. 5-eligible homeowners, this additional supply would simply be meeting a corresponding increase in demand that is also due to Prop. 5 — in other words, Prop. 5 would do little to address the state’s current shortage of housing. In short, Prop. 5’s effects on housing supply and mobility would be marginal, and largely accrue to a set of homeowners in California who can already afford to move.

What Would Proposition 5 Mean for Public Services?

Proposition 5 Would Reduce Funding for Local Governments

Prop. 5 would reduce funding for local governments including cities, counties, and school districts. This is because the measure would reduce the taxes paid from people who would have moved anyway. The LAO notes that, at current, about 85,000 homeowners who are 55 and older move to different homes each year without receiving the tax break provided by Prop. 5, resulting in these homeowners paying higher property taxes.[20] Prop. 5 would reduce their property taxes and, therefore, reduce property tax revenue available to local governments. Prop. 5’s tax break would result in more people moving, with the number of movers increasing by “a few tens of thousands,” and could also have some effect on home prices and home building that would lead to more property tax revenue.[21] Since Prop. 5 would increase home sales it would also affect local property transfer taxes collected by cities and counties, likely in the tens of millions of dollars per year. The LAO analysis finds that the potential revenue losses from people who would have moved anyway are larger than the gains from higher home prices and home building. As a result, property tax revenues available to local governments would be reduced. In the first few years, the losses would be over $100 million per year for local governments and over $100 million per year for school districts, growing to approximately $1 billion annually for both over time.[22]

Reductions in local property tax revenue caused by Prop. 5 would decrease the amount of funding available for an array of local government services including schools, police, fire services, housing, infrastructure, and human services. The reduction in local property tax revenues would also lower local governments’ bonding capacity — the ability to issue bonds to finance local infrastructure projects.

What Would Proposition 5 Mean for Total K-14 Education Funding?

Prop. 5 would reduce the amount of annual property tax revenue available to K-12 school and community college districts by about $1 billion over time, according to the LAO.[23] In most years, however, the total amount of dollars provided to K-14 education statewide would not be affected by this reduction in local property tax revenue, due to provisions in California’s Constitution — added by Prop. 98 in 1988 — that guarantee K-14 education a minimum level of funding each year.

Under the Prop. 98 guarantee, two revenue sources together fulfill the state’s funding requirement for K-14 education: local property tax revenue and state General Fund dollars.[24] In most years, property tax revenue represents the first dollars applied toward meeting the Prop. 98 minimum guarantee, and the state’s General Fund fills the gap between the property tax revenue and the minimum funding level.[25] In such years, reductions to local property taxes under Prop. 5 would not affect the total amount of K-14 education funding statewide. This is because any reduction in property taxes would be offset by a corresponding increase in the amount of state General Fund dollars used to fulfill the Prop. 98 guarantee. In these years, the fiscal effects of extending property tax advantages to older homeowners under Prop. 5 would come at the expense of other vital state services that are supported with state General Fund dollars.

In certain other years, however, total K-14 education funding declines dollar for dollar with any reduction in property tax revenue. In these years, an alternative provision of Prop. 98 (known as “Test 1”) requires the state to provide K-12 schools and community colleges with a specific percentage of total General Fund revenue regardless of the amount of local property taxes that K-14 districts receive.[26] As a result, to the extent that Prop. 5 reduces local property tax revenue in Test 1 years, the total Prop. 98 funding level for K-14 education would fall because the state would not be required to spend General Fund dollars to make up the difference. Moreover, any reduction to local property tax revenue in a Test 1 year could affect calculations of the Prop. 98 guarantee in future years because the base for calculating the guarantee in most years is the prior-year Prop. 98 funding level.

Proposition 5 Would Reduce Funding for Some K-12 School and Community College Districts

While Prop. 5 would reduce local property taxes for K-14 education statewide, total annual revenue for most individual districts would not change. This is due to the difference between formulas in the state Constitution that determine the annual Prop. 98 funding guarantee for K-14 education and other formulas in state law that determine the amount of dollars allocated to individual K-12 school and community college districts. Annual revenue for a large majority of the state’s individual K-14 districts comes from a combination of sources that include local property taxes and the state budget. For these districts, reductions in local property taxes are backfilled by the state.[27] As a result, most California K-14 districts would not experience a change in their total revenue if Prop. 5 reduces the amount they receive from local property taxes.

In contrast, reductions in local property taxes under Prop. 5 would decrease funding for a small but significant share of K-12 and community college districts. Roughly 10% of California’s K-14 districts receive local property tax revenue beyond the amount of funding to which they are entitled based on formulas in state law.[28] The state does not backfill reductions in local property tax revenue for these so-called “excess tax” districts.[29] As a result, any decline in local property taxes caused by Prop. 5 would mean a dollar-for-dollar reduction in funding for K-12 school and community college “excess tax” districts.

What Would Proposition 5 Mean for the State Budget?

Prop. 5 would increase state spending to support K-14 education and, in turn, reduce the amount of General Fund dollars available for other state budget priorities. Over time, the LAO estimates that the measure would cause annual state spending for K-14 districts to increase by about $1 billion, though without raising the total amount of funds available to schools and community colleges.[30] This is because, as described above, Prop. 5 would reduce the amount of property tax revenue received by K-14 districts, which in most years would require the state General Fund to backfill the local property tax shortfall dollar-for-dollar up to the total funding level required by the Prop. 98 funding guarantee.[31] In these years, reductions in local property tax revenue caused by Prop. 5 would reduce funding available for programs other than K-14 education, such as health care, housing, human services, and higher education.

What Do Proponents Argue?

Proponents of Prop. 5, which is sponsored by the California Association of Realtors, include the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, Californians for Disability Rights, Inc., and the California Senior Advocates League. Proponents argue that the measure “gives all seniors (55+) and severely disabled the right to move without penalty” and “empowers retirees living on fixed incomes.”[32] They state that “Prop. 5 helps Californians who want the opportunity to move,” “does not take funding away from public schools,” and “does not take funding away from public safety.”[33]

What Do Opponents Argue?

Opponents of Prop. 5 include the California State Association of Counties, Middle Class Taxpayers Association, National Housing Law Project, California Alliance for Retired Americans, and the League of Women Voters of California. Opponents argue that Prop. 5 will “further raise the cost of housing,” and “lead to hundreds of millions of dollars and potentially $1 billion in local revenue losses” and that it “gives a huge tax break to wealthy Californians.”[34] Opponents state that “Prop. 5 does nothing to help most low-income seniors but does help corporate real estate interests who are funding it.”[35]

Conclusion

Prop. 5 would make changes to California’s local property tax system by significantly expanding tax breaks for certain property owners. These tax breaks would provide advantages to older, wealthier homeowners at the expense of younger, less affluent homeowners and would do little to address the state’s current housing shortage. Voters should weigh Prop. 5’s tax breaks against annual revenue losses that would reduce funding available for local services and state programs. Prop. 5 would reduce annual funding for local governments by $1 billion over time, dollars that would no longer be available to support an array of local services including schools, police, fire services, housing, infrastructure, and human services. Another important consideration is the measure’s impact on the state budget. Prop. 5 in most years would reduce funding available to the state by $1 billion over time for key programs such as health care, housing, human services, and higher education.

Endnotes

[1] For a comprehensive discussion of Prop. 13, see California Budget & Policy Center, Proposition 13: Its Impact on California and Implications (April 1997).

[2] A property is considered substantially damaged or destroyed if the physical damage it sustains is more than 50% of its value immediately before the disaster. California Constitution, Article XIIIA, Section 2(f)(1).

[3] For a detailed definition of “qualified contaminated property,” see California Constitution, Article XIIIA, Section 2(i)(2).

[4] California Constitution, Article XIIIA, Section 2(a).

[5] The 11 counties that allow inter-county transfers are Alameda, El Dorado, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Tuolumne, and Ventura. However, El Dorado County repealed its acceptance of inter-county transfers effective November 7, 2018.

[6] SB 1692 (Petris, Chapter 897 of 1996) created one exception to this one-time limit by allowing homeowners age 55 or older who transfer the taxable value of existing property to a new home to do so twice in a lifetime if they subsequently become disabled.

[7] California counties also may allow owners of contaminated property to transfer their taxable value from another county to a property that is acquired or newly constructed in their county.

[8] Property owners can still transfer the assessed value of a damaged or destroyed property to a replacement property that is greater than 120% of the market value of the destroyed property, but any amount over the 120% threshold is assessed at the full market value and added to the taxable value of the destroyed property.

[9] As noted above, these rules apply to homes purchased in the same county and in 11 California counties that allow older homeowners to transfer the taxable value of homes sold in a different county to a home purchased in their county.

[10] The taxable value of property typically increases each year based on an inflation adjustment that Prop. 13 limits to no more than 2% annually. This Issue Brief does not include annual inflation adjustments in calculations of annual property taxes in order to simplify the discussion.

[11] Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 37.

[12] Office of the State Treasurer, California Bonds 101: A Citizen’s Guide to General Obligation Bonds (2016), p. 1.

[13] As noted earlier, owners of property that has been substantially damaged or destroyed by disaster or contamination would also be eligible for the special property tax rules under Prop. 5. However, these owners would likely make up a very small share of the total number of eligible property owners. For example, the 2017 Tubbs Fire in Napa and Sonoma counties — the most destructive in California history as of August 2018 — destroyed 5,636 structures, a tiny number compared to the 4.0 million households estimated to be eligible under Prop. 5 due to the age of the homeowner.

[14] Unless otherwise indicated, all statistics in this section are from a Budget Center analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey data for 2016.

[15] The Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) notes that about 85,000 homeowners age 55 or older currently move to different homes each year without receiving a tax break, and estimates that the number moving might increase by “a few tens of thousands” if Prop. 5 were to pass. See Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, pp. 36-37.

[16] The California Poverty Measure (CPM) is a state-specific measure of poverty modeled on the US Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure. The CPM provides a more accurate measure of economic hardship than the official federal poverty measure and is particularly appropriate to measure poverty for this analysis, because it accounts for local differences in the cost of housing and differences in housing costs across renters, homeowners with mortgages, and homeowners without mortgages, among other improvements. See https://inequality.stanford.edu/publications/research-reports/california-poverty-measure.

[17] Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 37.

[18] Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 37.

[19] Department of Housing and Community Development, California’s Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities (February 2018), p. 5.

[20] Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 36.

[21] Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 37.

[22] The LAO’s long-term estimates reflect inflation-adjusted figures. Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 36.

[23] The LAO’s estimate reflects annual property tax losses adjusted for inflation. See Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 37.

[24] Prop. 98 states that K-14 education is guaranteed an annual funding level that is the greater of a fixed percentage of state General Fund revenues (Test 1) or the amount that K-12 schools and community colleges received in the prior year, adjusted for enrollment and changes in the state’s economy (Test 2 and Test 3). For an explanation of the Prop. 98 guarantee, see California Budget & Policy Center, School Finance in California and the Proposition 98 Guarantee (April 2006).

[25] In Test 2 and Test 3 years, the state is required to provide General Fund dollars equal to the funding level guaranteed under Prop. 98 less local property tax revenue provided to K-12 schools and community colleges.

[26] Test 1 has been operative five times since the Prop. 98 guarantee was established in 1988-89 and ties the minimum funding level for K-14 education to a percentage of General Fund revenue, which has ranged from 35% to 41%. For a description of the history of Prop. 98, see Legislative Analyst’s Office, A Historical Review of Proposition 98 (January 2017).

[27] Under current formulas in state law, reductions in local property taxes for individual K-14 districts are backfilled by the state even in Prop. 98 Test 1 years when reductions in overall statewide local property tax revenue cause the Prop. 98 guarantee to fall.

[28] In 2017-18, so-called “excess tax” districts, excluding county offices of education, comprised 10.6% of K-12 school districts and 9.7% of community college districts.

[29] Similarly, any boost to the amount of property taxes that “excess tax” districts receive results in a dollar-for-dollar increase in their total funding.

[30] The LAO’s estimate reflects annual state spending for K-14 education adjusted for inflation. See Legislative Analyst’s Office, “Proposition 5. Changes Requirements for Certain Property Owners to Transfer Their Property Tax Base to Replacement Property. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. Analysis by the Legislative Analyst,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 37.

[31] As noted above, in Prop. 98 Test 2 and Test 3 years the state is required to provide General Fund dollars equal to the funding level guaranteed under Prop. 98 less local property tax revenue provided to K-12 schools and community colleges.

[32] “Argument in Favor of Proposition 5,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 38.

[33] “Rebuttal to Argument Against Proposition 5,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 39.

[34] “Argument Against Proposition 5,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 39.

[35] “Rebuttal to Argument in Favor of Proposition 5,” in Secretary of State’s Office, California General Election Tuesday November 6, 2018: Official Voter Information Guide, p. 38.